.

Matteo graduated from University in Economics and started full time studying photography and filming. He started taking pictures just before he started climbing, then he combined the two activity and, without even realizing it, it became simply more than just a passion. He thought it could stop at some point, but then that passion continued to grow and change shades. Ten years ago he skipped lessons at the University to go climbing and take pictures of those who at the time were the strongest climbers in Italy (who often passed in his area and who soon became important friends). After a three-year degree in Economics and Management, he decided to leave a career to focus full time on photography and video. He soon started shooting for clients like La Sportiva, Mammut, Patagonia, making publications for National Geographic, Profoto, RedBull and working top-class athletes. Currently, in addition to working for some of the important companies in the outdoor sector, he’s focusing on photographic and video reportage on environmental themes, trying to combine aesthetics with social utility.

Words and images by Matteo Pavana

As soon as I decided that I would have followed Simone Moro and Tamara Lunger on a winter expedition, I already knew that a great adventure was starting for me. Their main intention was to climb the peaks of Gasherbrum I and Gasherbrum II, something that only Reinhold Messner and Hans Kammerlander did 35 years ago. Simone and Tamara wanted to repeat the ascent but in the winter season. These two peaks are located in the remote Karakorum valley in Pakistan. Not far from the Gasherbrums there are two other eight thousand meter peaks: the Broad Peak and the K2. I want to be clear: climbing an 8000m is a feat that has succeeded in thousands of people since alpinism exists. Only about twenty people managed to climb an 8000m peak in winter. Simone is one of these climbers and, more specifically, he is the only one in history to have climbed the first four of the fourteen eight thousand meter peaks in the coldest season.

I’ve been dreaming of going on an expedition for years. I grew up with the myth of the great explorers and the great climbers. For example, Vittorio Sella, a well-known Italian mountaineer, and photographer photographed these mountains for the first time in 1899, at a time when entering the Baltoro glacier was already a huge human achievement. I’ve always desired to live for a long time far from civilization, in a hostile and real environment. This expedition was the crowning of a dream for me. I was lucky enough to be able to reconcile an important job assignment together with a work of personal inner introspection.

The rhythm of my life is sometimes so fast that I feel drowned, I cannot fully enjoy the experiences that I am living...

Together with me in this adventure, there were Simone Moro, Tamara Lunger, and the photographer/filmmaker Matteo Zanga.

The month before the expedition was a nightmare for me.

I cannot hide that I was often taken by doubts regarding my choice because I was afraid of not being up to it, that I would not have resisted to the cold temperatures or that in any case, something would have gone wrong, that I would not have been able to it. On the other hand, following the most adventurous climbers in the world requires physical as well as psychological preparation. So I stopped thinking too much and I started getting motivated by all those doubts. That’s what exploration is made of: uncertainty.

Winter expedition means deep cold.

I knew that the cold would have been my worst enemy throughout the expedition, night or day it was. "Fighting the cold" I don't even think it's a correct expression since it's invisible. You can only stand the cold, although once we arrived at the base camp we had a kerosene stove and a gas heater. But during the eight days and the 120 km of trekking approaching the base camp, the cold was an unpleasant companion. In fact, arriving only at the Gasherbrum base camp is an adventure in itself. Generally, all climbers who want to go to that place fly by plane to Islamabad, from Islamabad, when the weather permits, fly directly to Skardu (the real gateway to the 8000m peaks in Karakorum). When a flight is not an available option, the only alternative is to travel on the KKH, the highest paved road in the world that connects Pakistan with China. Once we arrived at the village of Bungi we turned to Skardu and finally to Askole, which corresponds to the beginning of the approach trekking.

It's amazing how the human body gets used to the cold with time and how, once the expedition is over, you feel nostalgia for the unpleasant feeling. There were starry nights where temperatures plunged radically reaching peaks of -35 degrees. I don’t miss those terrible nights, but I miss that incredible clear sky full of stars.

I learned and accepted the cold. With the passing of days, I developed a sense that doesn't belong to me at all: patience. Patience towards that slow time, that empty space and the immensity and fullness of the uninhabited mountain. The moment I was really starting to understand the reason for that experience, the accident happened.

On 18th January 2020, Simone fell into the crevasse. The Gasherbrum icefall was very dangerous, this year more than ever. It took only a second: a snow bridge collapsed and Simone fell 20 meters into a crevasse. Tamara, who was belaying him, was pushed by gravity towards the crevasse, stopping 50 centimeters from its edge. Simone and Tamara wore snowshoes as they were the only suitable tool to move in that snowy, trying to avoid the risk of sinking too much while they’re walking and at the same time not overloading the bridges of snow. When everything seemed to be perfect (between weather forecasts, mountain conditions and the physical fitness of the climbers) everything ended, like a blink of an eye.

The expeditions to the highest mountains in the world reminded me of how blurred is the boundary between life and death, between success and tragedy. Surely for me, that I’m always trying to push my personal limit in the mountains, something in that place has been different. I understood that you can never underestimate the risk in the mountains, especially those mountains. Everything in those places is so big, that preparation and self-control sometimes are just not enough. Acceptance of this limit is fundamental for your own survival.

There was a specific moment during the expedition when I asked myself what was the boundary between being a photographer and being a mountaineer. That boundary corresponds to your responsibility. I was not able to define risk, I was not capable of it. One day I entered the glacier with Simone and Tamara: we walked in the easy part of the glacier, where the seracs and crevasses were still small compared to the upper part. Although my advanced mountaineering and climbing skills, I felt so uncomfortable, unprepared, alone.

Many people asked me: how did you shoot in those harsh conditions? What kind of gear did you take with you on the expedition? How did you backup all the data?

For this expedition, I had the opportunity to be supported by Sony Italia. I told them the necessity to have a top-class camera gear that can be performing at really low temperatures.

You can find Matteo's work on his Instagram and Website.

"We Are f-stop" is for all f-stop users to share their stories from the field, from small daily adventures to epic travels. Contact us with your story on Facebook or drop us an email to [email protected] and let us know where your photography takes you and your f-stop pack!

SHOP ALL GEAR MORE WE ARE f-stop

©2022 F-stop

Ryan is a photographer and broadcast cameraman working on adventure, travel and wildlife documentaries. As a freelancer, he works on shoots across the world for clients ranging from the Discovery Channel to the BBC’s prestigious natural history unit. Since studying documentary photography, Ryan has made a name for himself as a specialist in high altitude mountain and cold environments where he is at home on foot, crampon, rock wall or ski, and other environments requiring awkward or technical access and movement. He’s worked in environments ranging from 5000m above sea level down to 2KM deep underground.

Words and images by Ryan Atkinson

For those of us blessed with the natural mediocrity of the British Isles, the challenges of an ever globalized threat from a changing climate are a stretch of the imagination at best. The distant and dry valleys of the Hindi Kush Himalaya register little, if at all, on the radar of public discourse in a country that complains at its worst of too much water. Yet with globalization comes decreased distances, and the knock-on our door of an ever-changing world. A world where the water we so oft complain of on our own shores would be a welcome respite from a life lived in desiccation around the earth.

How does one face this change, this struggle, as an adventurer? By nature of purpose, my life is a black mark on the carbon history of the world. Individual, sure. Small, indeed. Insignificant, no. In a world of likes and shares, responsibility is ever so collective. Long flights to remote corners of the world register at the moment as little more than a cramped inconvenience, consumed in the throes of limited legroom and time zones crossed. Time lost. So when the opportunity to travel to the depths of the world's lowest valleys and the caps of it’s highest mountains came knocking on my very local door, I opened it. Landing in a polluted Kathmandu on a rainy autumn day, the thrill was all that filled my mind. In the footsteps of all those boundaries expanding Brits that went before me, I was here for the mountains. Here to tell a geographic story of excitement and loss. It was the landscape that drew me, but it was the people that marked me.

Still scarred by the horrors of the 2015 earthquake, the Langtang Valley was our destination. A valley marked with rock and loss. Loose mountainsides where ice was once the glue. Towns lost under the rubble of a changing biome. Mighty peaks are strewn in the valleys, burying generations and stories lost. Emptiness at height, where great rivers of ice once fed this mighty watershed. A world turned upside down by the consumption of my forefathers a globe away. Of myself. The journey progresses through these valleys, and with eyes turned towards the goal above me, I very soon come to realize that the story I’ve come to tell lies not at the top, but at the bottom. The striking thing about traveling through the highest mountains of the world isn’t the snow-capped peaks, but the humanity living in the long-cast shadows. Generations of wisdom, tenacity, suffering, and joy etched into every friendly and curious face we meet. Happy and content, these are people like no other; with so little but so much. Choosing simple rural toil over urban chaos and promised riches. A life devoid of the luxuries of development. A life devoid of the cause and yet marked by the effect. Rivers running dry and cliff sides perilously leering toward their upward gaze. Yet here they are, and here they choose.

After the 2015 earthquake, entire towns were lost. Blame for nature’s troubles cannot lie solely with humanity's presence, and yet the question hangs heavy over these dark valleys. I begin to wonder if it is not the commanding summits, but the weight of that question that casts the shadow in the depths of my mind; what if? What if there were no cars? No factories? No unfettered consumption? As distant to my doorstep as the threat of glacial collapse, these are people with no contribution to the woes that now befall them. And yet here they live. And they rebuild. Forever looking forward and upwards to their holy peaks. The Climate Crisis is beginning to show as another line etched into their faces, old and young alike. The loss of life-giving glaciers and the threat of these mighty bastions collapsing under the weight of all humanity, another worry added to a life already so full of uncertainty. Yet onwards and upwards they go, choosing not to blame but resolving to survive and thrive, summiting their own struggles beneath the watchful eye of the mountains. This blameless love of life leaves me to consider my own troubles, no less valid, and yet all the more real to me. We are separated by oceans and mountains, yet my opulent life directly makes theirs harder. I resolve to take their story home with me, and carry it with me everywhere I travel; a marker for the reality of a global crisis on a local level.

I came here for the mountains. But I left with the people.

You can find Ryan's work on his website, Instagram and Facebook.

"We Are f-stop" is for all f-stop users to share their stories from the field, from small daily adventures to epic travels. Contact us with your story on Facebook or drop us an email to [email protected] and let us know where your photography takes you and your f-stop pack!

SHOP ALL GEAR MORE WE ARE f-stop

©2022 F-stop

Kieran specializes in off-grid adventures, travel films, documentaries, and ambitious branded content.

In 2019, he co-founded London-based production company Seeing Shapes Films alongside friend and filmmaker Matt Farman. Later that year, they entered a travel film "Unbeknown" into the ROAM awards which took first place in the "Awe" Category.

As a diehard explorer, Kieran is known for his unrivaled energy and natural ability to connect with people, which imbues his stories with authenticity and emotion. From ice fishing in the Arctic and scaling desert dunes in the Middle East to hiking volcanoes on the Pacific Island of Vanuatu, he is a passionate professional, thriving behind the camera wherever in the world he may be.

Words and images by Kieran Hodges | Owen Tootill | Jason Wright

I’d seen the Yakkel village online a few years ago. I’d wanted to visit, so when a last-minute gap opened up in my schedule, I thought, ‘this could be the time.’ I was in London and would have had to leave in a few days, but I didn’t have contact on the island. I tried speaking to travel companies on the mainland of Port Villa but wasn’t making much progress. Eventually, I connected with Tom, the only person in the Yakkel village with a mobile phone. I called him from my office in central London, introduced myself and told him I’d like to come and visit. He was excited and we hatched a plan. I’d fly to Vanuatu and meet Tom and he would take me to his village where I’d be welcomed to live with him and shoot some film.

A trip like this is always made better with company. I called two of my friends who live in Brisbane, Australia, a short flight to Vanuatu. It was a long shot inviting them, they’d have to drop everything in the next couple of days to come along, but they didn’t need much convincing. We flew to Tanna Island Airport where we were greeted by Tom with hugs and smiles. Then, aboard a pick-up, through the jungle for two hours to his home.

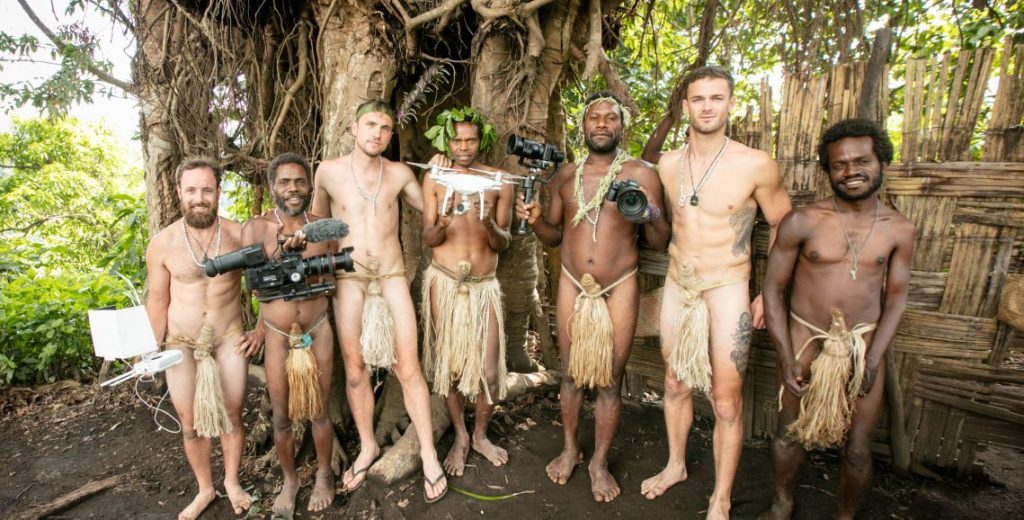

The men of the village wore nambas – a simple sheath made from grass.

In our jeans and T-shirts, we felt a little out of place. We asked our host, Tom if we might swap our clothes for the Yakkel get-up. 'Are you sure?’ asked Tom. We were certain so said 'of course'.

Tom led us down into the bush, where we stripped off, swapping our boxers for nambas – a look that doesn’t leave much to the imagination and had us feeling pretty exposed before we’d settled in. The new outfits were a hit with the villagers, who pointed and laughed, smiling and chatting amongst themselves. We had attempted to immerse ourselves in the Yakkel culture, to experience and integrate and we felt accepted. Whenever I’m filming and shooting people in remote locations, it’s essential to be humble, to show respect and to offer yourself to every experience. Plus, walking around the jungle in a nambas is liberating, I’d highly recommend it.

Our goal for the next four days on Tanna Island was simple: we wanted to connect with the community, learn their way of life and develop deep connections through sharing culture, film and photography.

One of the main attractions on Tanna is Mount Yassur, an active Volcano that sits 361 meters above sea level. It was the glow of the volcano that apparently attracted Captain James Cook on the first European journey to the island in 1774. We had arranged a 4x4 to take us to the coast to visit the Volcano in the early hours of the morning. Some of Tom’s family had never seen Yassur before, so we filled the pick-up with camera gear and we all piled in.

Nearing the summit of Yassur, the swirling lava storm is a sight to behold. Those moments where you feel your human fallibility, your smallness in the universe and the power of the natural world - this was one of those moments, felt by every one of us that day.

For myself, Owen and Jason, close friends I’d been filming with for years, this was a once-in-a-lifetime trip. We’d never repeat this again, not in the way it had all panned out – the energy, the connections, the experiences. In Vanuatu, we made connections with the Yakkel villagers that transcended language and we shared moments I’ll never forget. Signing off, we exchanged gifts with the village Chiefs and took a few final pictures together. Then away from Tanna with our footage immortalizing those great moments – a trip to the soul of the island.

You can find Kieran's work on his Instagram and Website.

"We Are f-stop" is for all f-stop users to share their stories from the field, from small daily adventures to epic travels. Contact us with your story on Facebook or drop us an email to [email protected] and let us know where your photography takes you and your f-stop pack!

SHOP ALL GEAR MORE WE ARE f-stop

©2022 F-stop

He is not just a photographer – he is a sportive that made his passion a work. Climbing, MTB, freeride ski, trail running are the sports that Luca loves to photograph.

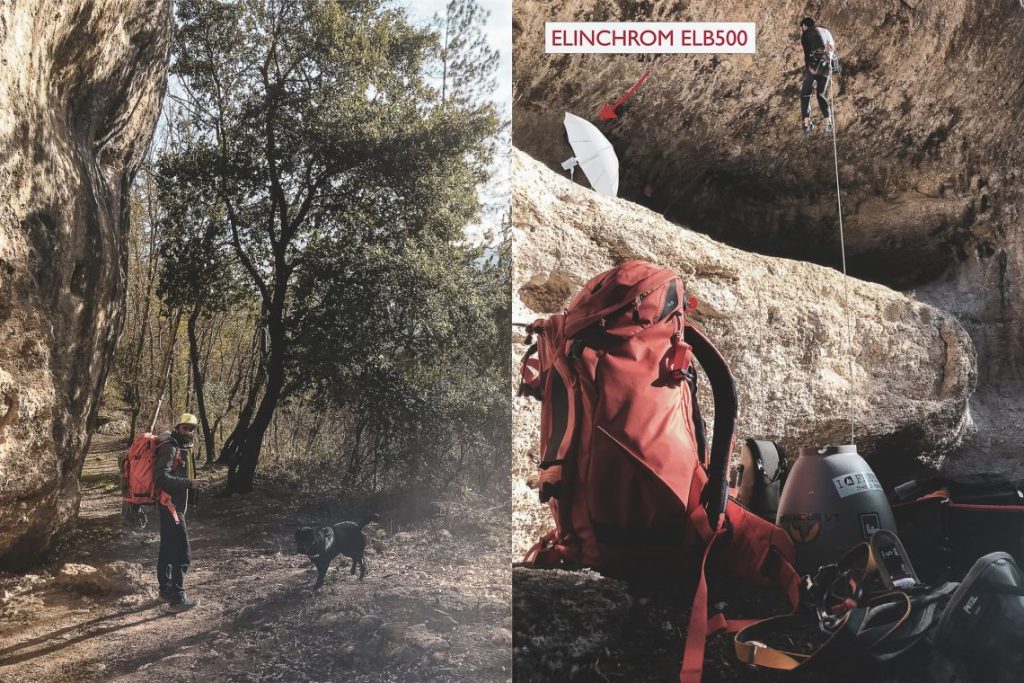

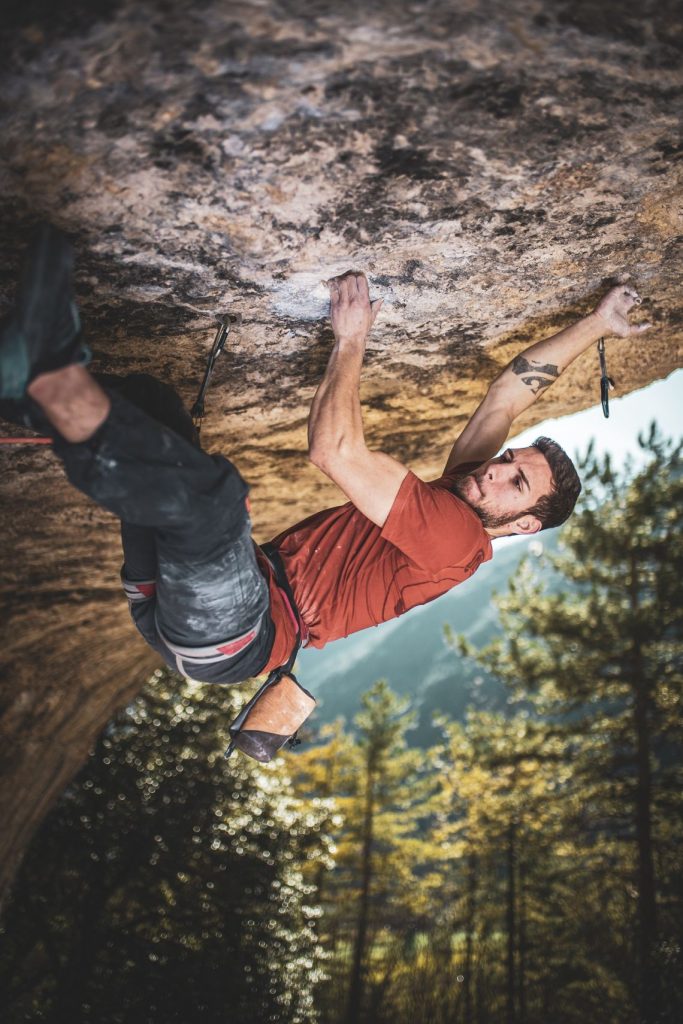

Luca recently went on a trip to Grotti with climber Elias Iagnemma to shoot on the hardest climbing route in the Lazio region.

Words and images by Luca Parisse

Many weeks ago I went to Grotti (Ri, Italy) to shoot the strong climber Elias Iagnemma in action on the hardest climbing route in Lazio region: “Last Tango at Zagarolo” 9a/9a+

To carry the equipment I used the f-stop Tilopa, with a Large Pro ICU. This was the equipment that I had inside:

Canon 1DX MKII body, three lenses (canon 16-35mm f2,8L II, sigma 35mm f1,4 Art and canon 24-105 f4 L) and the Elinchrom ELB500 Flash with the action head and the Skyport Pro Transmitter. In the front and laterals pockets I had: harness, carabiners, handle ascender and a belay device. Outside the bag, I had the rope.

Firstly, I shot the first section of the route that was inside a dark cave with a very bright sun outside. For this reason, I used the flash with a big umbrella as a diffuser in order to achieve both the proper light on the climber and the correct exposure on the background.

I got the background exposure first and then I turned the flash power to light up the cave and the climber.

I shot with a wide-angle lens to capture most of the cave but without getting the poetic bokeh effect in the background.

So I also used one of my favorite lenses: the Sigma 35mm f1,4 Art Series. Thanks to the hypersinc function of my flash I was able to exploit the full lens aperture without ND filters. This way I obtained very cool painting-like pictures.

To shot the second part of the route I climbed about 20 meters using a fixed rope, a handle ascender, and a belay device.

I carried the camera with Canon 24-105L lens in the small f-stop Navin secured to the harness.

I hope you found these tips interesting!

Be creative and have fun!

You can find Luca's work on his website, Instagram and Facebook.

"We Are f-stop" is for all f-stop users to share their stories from the field, from small daily adventures to epic travels. Contact us with your story on Facebook or drop us an email to [email protected] and let us know where your photography takes you and your f-stop pack!

SHOP ALL GEAR MORE WE ARE f-stop

©2022 F-stop

.

Heath's work has been primarily based around editorial assignments for newspapers, magazines and wire agencies for many years. He is currently in Nairobi, Kenya and has been for the past 3 months working to develop some documentary photography skills for longer projects. He has held a few staff positions throughout his career in various countries, Singapore 2009-2011 and most recently in 2018 in Doha, Qatar. He has always been a very curious person so whether it’s human interest, adventure-based or wildlife/nature conservation he’ll go for it. From here he will spend his time between Africa and the Middle East, working to build a base with access to interesting opportunities.

Words and images by Heath Holden

In early November I traveled to the small island of Lamu on Kenya’s northern coast. I had been told about Lamu many times since arriving in Kenya late in August but didn’t pay too much notice as my attention was directed at some conservation trips into the Samburu in Northern Kenya with the Grevy’s Zebra Trust. When I left Australia I intentionally packed two specific issues of National Geographic magazine, one with a story on the coast of East Africa which I had skimmed through earlier but had not finished, and one with a story on Sicily… One afternoon I found myself looking for the magazine to finish the article, it was called “Swahili Coast, East Africa’s Ancient Crossroads” and is in the October 2001 issue, it was very interesting and became the final catalyst for my ticket purchase. Lamu “old town” is still very authentic and has been listed as a UNESCO heritage site.

After spending over 12 months in the Arabian Gulf working in Qatar, I have found myself becoming more interested in photographing the Arabic influence on regions outside of the Middle East. Lamu is a historical trading post between the African people and the seafaring Arabs and Indians, so there are clear Arabic and Indian influences on the island, especially food, language, and faith. The trade included but is probably not limited to timber, animal skins, ivory, spices, cotton, silk, gold and... slaves. During my stay the Maulid Festival was scheduled so I extended my time on the island from 10 to 16 days, the festival is an Islamic celebration for the birth of Prophet Mohammed and is a week of music, dance and prayers.

Traveling solo, I was looking forward to wandering the endless alleyways in search of life’s daily moments, going light with two small cameras - a Leica Q which is a 28mm Summilux and a Leica M262 with a 50mm Summarit, and at times a flash, but rarely, all packed into an f-stop Gear Base Camp 100. I walked for hours observing, taking mental notes, early mornings turned into evenings which turned into night as locals commuted to work, hustled along the seafront, unloaded the fish and took shelter as the storms rolled in.

The trip was tiring and overwhelming as I wanted to be everywhere, and damn I tried, this is my story of Lamu and the people who call it home.

Lamu, and most of the Kenyan coast for that matter is an Islamic region and cultural beliefs are very conservative and opposed to being photographed without some kind of consent, this definitely causes challenges and makes it quite difficult to photograph the authentic street scenes I was after. You will never go unnoticed, I would often hear “No photos” even when I was nowhere near holding a camera. However, this is not absolute and there was a small percentage who were ok with it, and also those who would comfortably pass through a scene knowing I was likely taking a photograph. One other challenge I continuously encountered was meeting street sellers, I would have one guy who could sell me everything, a town tour, a sunset dhow cruise, an oil painting which he hand-painted at his studio and a turtle to take back to Ireland, the list goes on…

After more than 2 weeks walking around a small African island town, locals know you, they might begin to ever so slightly accept your presence, not completely, but slightly, this is where your tolerance and patience will be essential.

During my time in Lamu, there were some heavy rains, it was a nice change to the constant hot sun and it brought a different mood to town. The kids were out running through floods and racing donkeys through the alleyways when the downpours ceased and the sun shone through the clouds again the light was magical, champagne as William Albert Allard would describe it. The palette would become extremely vibrant and I would move to some known locations which would work for an observe and wait technique. Food, when is food not good? Island life means seafood, big meaty crabs, lobster and fish, also a few good pizzas and lots of fruit!

From my experience over the past decade working as a photographer, I would simply say to approach such locations with an extremely open mind, you might have some visual ideas and maybe even a shot list if you’re trying to please someone, but really just get out and hit the streets early, work late, get tired discover in real-time. Be respectful to the culture and if you are ever unsure, ask someone at your hotel. I know, very general but it works.

You can find Heath's work on his website, Instagram and Facebook.

"We Are f-stop" is for all f-stop users to share their stories from the field, from small daily adventures to epic travels. Contact us with your story on Facebook or drop us an email to [email protected] and let us know where your photography takes you and your f-stop pack!

SHOP ALL GEAR MORE WE ARE f-stop

©2022 F-stop

The Fifty Project - Skier Cody Townsend and cinematographer/director Bjarne Salen are trying to climb and ski all 50 classic ski descents of North America, based on the book 50 Classic Ski Descents of North America. These lines are some of the most challenging and spectacular ski descents in the continent.

It’s a 3-year project and one episode for each ski line is released online, for free, on Cody Townsend’s YouTube Channel every other Wednesday all winter.

Words and images by Bjarne Salen

f-stop: Let’s talk gear, what equipment do you normally carry for your shoots?

Bjarne: Overall I use different camera bags depending on the objective of the day, and what gear is necessary. The bigger the mountain, usually the less gear I bring. Shorter days usually allow me to bring more gear.

For The Fifty Project, I tend to keep gear to a minimum. If it’s too heavy, it takes too much time to set up and shoot, which then becomes dangerous in the mountains if you are too slow.

For packs, I use either a Tilopa or Loka UL. Then on my hips, a lens barrel to have one lens on one side and then a Navin on the other side on my hip. They are attached to my hip belt of my backpack.

This allows me to have quick access to the camera; I don’t have to take the pack off my back and I can shoot in the mountain where ever I am. Even if I hang in a harness dangling down a couloir I can quickly access my camera and shoot.

If I pack my gear like this I feel safe, fast and can do my job quickly.

Other gears I use when I film in the mountains are crampons, ice axes, skins, food, water, down jacket, drone, batteries, monopod hanging from my pack, glasses, goggles, helmet, transceiver, shovel, probe, radios, and some Swedish fish as an extra snack on the summit of course. That’s the most essential one.

f-stop: There are probably a lot of things on your mind when you are preparing for this kind of project, what do you think are the biggest challenges?

Bjarne: There are many challenges that start during planning. Cody is researching a lot all over the country every day. We are checking weather and conditions all over the continent. He’s doing a lot of this research and has contacts everywhere, which are key. With all our combined research, we get a general idea if we should go and try the mountain or not. If we feel it's a green light and the snow is stable then we pull the trigger and go there. This can sometimes mean a last-minute, 12-hour road trip, so I always kind of have to be ready to go, wherever we are.

Scouting is another big part. When we arrive at a location we always have a few days where we look at the objective from far, walking in and checking it out a day or two before and seeing what happed with the snow and conditions the last 24 hours.

This can be challenging because you don't really know 100% how the conditions are before you are there in person.

If we decide to try and climb the mountain, then we take 30 minutes here and there along the way, to make crucial decisions and constantly evaluate and re-evaluate our risks. How are the snow conditions? Are we making a good time? Are we too late (which means it could be too warm and dangerous in the mountains), or do we still have a good window to make the summit…?

When it comes to all the filming I need to do along the way, there is a lot to think about in addition to our safety and risks. When packing, I need to have all camera equipment ready, set up, charged, and functioning, together with the all-mountain equipment we need for that climb. When we’re climbing, I think about all these things in a constant stream of thoughts: safety, planning, camera angles, what’s the story?, and always be one step ahead physically and mentally of the athletes, all day, to catch what might be happening for action or story (also make it look good and not put myself in danger if I’m out ahead of the group on my own). There is also a ton of training that goes into this in the offseason so I can be strong enough to make all this happen in the moment.

f-stop: What is next for you?

Bjarne: This project requires a minimum of 3 winter seasons to film, and we might continue longer now with this pandemic, who knows what will happen. We are more than halfway through the fifty mountains in the project, but in terms of the time it takes to climb each mountain, we are still quite far from halfway. Some of the mountains are weeks-long expeditions in remote places, plus all the planning and logistics that go into those expeditions to be able to climb and ski them safely. So for the moment, this project is my main focus for the foreseeable future.

During the off-season, I am working on several documentaries. I just released a new documentary about big-wave surfer Paige Alms, called PAIGE. It’s streaming on all major outlets, you can click this link to take you to the one nearest to you: https://geni.us/PAIGE .

I am also working on one of my biggest films so far - a feature-length documentary called Changing The Flow, which I hope to finish this year. It’s a story that spans over 12 years about the first all-female Nepali adventure guiding company, and the story of how they faced the odds over the years to make their dreams come true. I’m working on it with editor and producer Erin Galey, and we hope to get it out in the world very soon. Then I’ll be thinking about my next documentary project! You can find out more about it and see the trailer at www.changingtheflow.com .

You can find Bjarne's work on his website, Instagram and Facebook.

"We Are f-stop" is for all f-stop users to share their stories from the field, from small daily adventures to epic travels. Contact us with your story on Facebook or drop us an email to [email protected] and let us know where your photography takes you and your f-stop pack!

SHOP ALL GEAR MORE WE ARE f-stop

©2022 F-stop

f-stop Ambassador Jussi Grznar was on a trip with his friend Mason Mashon in Utah and he had an amazing story to share with us. Jussi is a photographer based in Vancouver, B.C, and is a storyteller at heart, always searching for the defining moment. His work has taken him through numerous mountain ranges, rice fields, double overhead barreling waves, and these kinds of experiences gave him a unique style of shooting.

Words and images by Jussi Grznar

Last November I chatted over the phone with my good friend Mason Mashon. He told me that he and his girlfriend Diane are planning on doing a road trip from British Columbia all the way down to Baja. The particular part of the trip I was interested in was Utah and California desert. Mason being a very creative human himself I knew we would find some beautiful zones to ride. Next thing you know we meet up in Hurricane, UT for what it turned out to be a pretty wild 2 week-long ride.

On day 2 I was walking down a hill after a great day of shooting. As I reached the last descent one of my feet slipped on loose gravel as I tried to run it out at the bottom I hit a ditched and crashed. I injured both of my legs and broke a rib. What actually broke my rib was the camera hanging on my shoulder. I broke both my camera and 70-200mm lens; whatever was in my backpack was fine. Lesson learned to put your equipment away once you are done shooting. On this trip I used my Tilopa which handled the elements really well (heat, sand and in this case the impact)

Getting out of the tent the next morning was quite the challenge. I was really debating if I should stay for a few more days or head home. Once I climbed out of the tent and saw how amazing our next zone was I decided to stay. I ended up shooting 8 more days, which I am glad I did as we got some great photographs.

To top what ended up being one of the best trips I’ve ever been part of on our last day our friend York from @iflyheli showed up. We flew around in his helicopter, got few aerial angles and finished the day flying through slot canyons. We couldn’t ask for a better end to our adventure.

You can find Jussi's work on his website, Instagram and Facebook.

"We Are f-stop" is for all f-stop users to share their stories from the field, from small daily adventures to epic travels. Contact us with your story on Facebook or drop us an email to [email protected] and let us know where your photography takes you and your f-stop pack!

SHOP ALL GEAR MORE WE ARE f-stop

©2022 F-stop

.

Alex grew bouncing between Northern and Southern California. He graduated with honors from San Diego State University with a degree in Television, Film, and New Media Studies. He has a deep passion for the outdoors, being active in all aspects of life. He’s summited Mount Shasta and snowboarded down, Mount Whitney too. He loves snowboarding, camping, ice hockey, backpacking, and just exploration in general. His side work ranges from aerial videography, photography, editing, graphics, and of course, video production. Alex is always striving to continue growth and self-development by learning and exploring. A goal of his is to travel to unique destinations, tell empowering stories through photo and video, and share it with the world. ‘Create more good, live to be your true individual self, then share that with the people around you.’

Words and images by Alex Hogue

“Hey Alex, would you be able to give me a hand?” The entire break area was littered with camera gear and accessories. Every type of case you would expect for production, was out, half-packed. Lenses, GoPros, light kits, sound equipment, f-stop bags, ICU’s, Pelican cases.. all of it scattered. I navigated the land-mine field as a parent would meticulously maneuver around a child’s legos. “Sure..where ya goin’ ?” I said to my friend Daniel who had one arm in a sling as he tried to stuff a 6-foot slider into a hard ski-case.

“The Seed Vault.” He said. A confused look washed over my face. I had no idea what a seed vault was, and it showed. Daniel continued, “This guy - Cary Fowler, built the ultimate backup doomsday seed vault in Svalbard. You know, in case we blow ourselves up and we lose a particular crop; like wheat. Could you imagine what that would do to the global food supply chain? (Life Pro Tip - when you hear the word ‘doomsday’ to describe something - it’s gotta be a place worth going to!) Well, that sounds cool I thought to myself as I asked: “Where’s Svalbard?” We tossed two Costco sized boxes of hand warmers into a nearby pelican case. “It’s about 650 miles from the North Pole. The northernmost settlement in the world.”

My friend and colleague Mario was also scheduled to go on this trip. Together, Mario and Daniel (with one arm in a sling) were to capture a ‘GoPro for a Cause’ story for the Global Crop Trust Foundation to raise awareness about the importance of preserving seeds and agriculture. There were about 13 bags of production gear, not including personal bags. About half of this was 360-VR gear, which was still a relatively new technology that required multiple rigs and cameras. I’ll let you do the math - but it’s easy to see where a few more hands would come in handy - literally.

I spent the next two days prepping and ravaging through REI (where I also worked part-time for 12 years). I loaded up on the thickest smart-wool socks I could find, along with some quality layers and shells. I previously lived in Jackson, WY for a winter season and knew what ‘cold’ felt like (It got to -25f a few nights!). But I had never been to the Arctic, so I didn’t want to skimp. During my time in Jackson, I worked for TGR - a ski/snow production company and ironically almost had a chance to go to Svalbard for the filming of Jeremy Jones ‘Further’ film. I knew it would be cold and my two-week production would be miserable if I brought the wrong attire. The inside of the Seed Vault was kept at -18c (or 0 F). Not exactly the stereotypical California flip-flop weather.

Together myself (Alex Hogue), Mario, and Daniel arrived at San Francisco International airport. We boarded a flight to Germany, then Oslo (Norway), Tromso (Norway), then Longyearbyen, Svalbard - a distant archipelago north of Norway. This was actually my first (ever) international travel, so even though travel took two days (with layovers) - I didn’t mind one bit

Over the next two weeks, our wolfpack trio would grow close and share some wonderful life moments (including how many times I would sacrifice my body for the sake of camera equipment while slipping on solid sheets of glacier ice with gear in-hand). I couldn’t have asked for a better crew.

Longyearbyen, Svalbard is your typical town suburban town. You know - you can’t leave town without a rifle, there are more polar bears than people, cats are illegal, and oh yea - it’s illegal to die there. True story, look it up.

Somehow all of our bags made it to this tiny airport which only has one flight daily. Massive win. My f-stop bag was on my back the entire time (I lied: it spent most of the time under the seat or in the overhead bin). It was my in-flight carry-on and had all the essentials: a lightweight jacket, travel pillow, laptop, DSLR, GoPro and a slew of snacks.

The next two weeks presented some challenges. We had envisioned these beautiful sunny shots - but it was overcast or snowy 85% of the time. When the sun came out, we dropped everything to get outside beauty shots (which also made continuity a bit challenging). In addition, as expected - the cold took a toll on the batteries. For timelapses and on the VR rig, and GoPro’s we would rubber band hand warmers around the cameras. Spare batteries for cameras, drones, lights, and audio gear had to be stored inside insulated soft lunch pales that I then stuffed into my Loka. Even with all this, the batteries would often die within minutes inside the seed vault. Suddenly all the extra equipment we brought that I thought was unnecessary was totally essential.

Another thing in the Arctic - the days are short (or non-existent) when we arrived, it looked like sunset all day long. How incredible is that? Each day we would gain about 20 minutes of sunlight. This meant a lot of low light filming, lugging around battery powered lights. There were times I thought my F-stop would burst open at the seams I had so much in there and strapped on. That never happened, not even close. It became obvious why high-quality gear is essential, you never know what you might need to do in those environments.

Some days our wolfpack and a local guide took snowmobiles for full day trips across the snow-covered tundra to capture b-roll. (Speaking of locals - the first thing I noticed about international travel is how big the world and cultures around us really are. Every single person I met was a prime example of a friendly, welcoming human being. This in itself was such a great eye-opener for me.) We became friends with our guides we would hire - because for them this was new and exciting, not just your everyday tourism tour. We got full VIP status treatment, and would then go our to share a beer the next night. Fridrik - one of our guides took us another day to an ice cave he had just discovered 2 days prior. Aside from him and his friend - no one had ever been in there to our knowledge. WOW. I have never felt more like a true explorer, and it’s because of him we got to go inside.

He backed up his snowmobile, anchored it deep in the snow and the 4 of us repelled down about 25 feet into a hole in the ground that had only seen its first human activity 2 days prior when Fridrik and his friend discovered it. This isn’t where he takes his tours, that’s for certain. The cave continued on for a few miles. We climbed, slid, and very carefully (so as not to damage) navigated our way through. Without lights, it was the darkest place ever. You couldn't see your hand if it was on your nose. It was cold, but without wind - it was very manageable and I was on such a high that I didn’t care. It took us about 3 or 4 hours to navigate through to another opening. All along the way, we recorded some of the most beautiful footage I have ever shot. Icicles from top and bottom - it was like walking through a crystal palace. We had no idea if this would ever make the video - but we had to shoot it anyways.

Since we had to crawl through tight sports, climb and repel - bringing a lot of gear was not an option. We each had f-stop bags loaded to the max some battery powered production lights, high-powered headlamps, water, meal packs, DSLR, and about 20 GoPro’s, some gimbals, a 4 foot slider, and more. Because of the tightness of the cave at times I would have to take off my f-stop Loka and slide it ahead of me, down a 30 yard ice slide by itself without things being damaged (Fridrik named it the penguin's slide).

On the snowmobile rides back we would rip through the snow, then go play in some deep snow, get the sleds stuck and do it all over again. We would have trailers behind our sleds, where the f-stop bags, and everything else would be strapped down. By the time we would stop, it would all be doused with snow and ice, but the bags held up.

Tips, tricks? What would I do differently? Honestly, our setup worked pretty well. For stuff like this, I would recommend keeping lots of carabiners and ways to attach things to your bag. At any given time I would be carrying multiple layers on me, sliders, tripods, hand warmers, and a slew of every GoPro mount imaginable. I also wish I would have found a way to carry my DSLR more so I could have gotten more personal shots. Since I was there for work on a GoPro production, I needed all the space I could get for necessary production gear. We were a small gorilla team, and carry travel capacity was a real concern. We had to be very selective about what to bring each leg of the shoot.

This was my first international trip to another world. Many years prior I told myself, “How cool would it be to travel to some crazy place to shoot a video.” As I got older, that idea developed more - I didn’t want it to be just any video. I wanted it to have a positive impact, I wanted to change the outlook of media as a whole. To teach and empower, instead of indoctrinating, fantasize and fear as many mass mediums do. Since then, I have done other international, and domestic trips for GoPro. Previously I also worked for production houses making videos for National Parks, Commercials and more. I’ve done all kinds of video /photo production, and editing; anything from your cousin's wedding to Super Bowl commercials. Some of my work can be seen on my website at www.AHDigitalMedia.com. But to really get the full picture, let’s connect. It’s the 21st century, come find me on the interwebs and tell me how this story impacts you. But first, let me share how it impacted me.

It was our final evening before catching an aluminum bird back to California. Riding the snowmobiles back toward the town of Longyearbyen, we stopped on the opposite side of the snowy fjord. Across the snowy fjord, we stared at the tiny town of Longyearbyen, a village nestled amongst a valley of mountains and permafrost. Tomorrow the locals would celebrate the changing of seasons. The sun would finally rise high enough in the sky to create the first direct sunlight on the church steps in many months. But tonight, the sun was setting, very slowly. It was then that I had a life-changing memorable moment. March 6th, 2016, 17 years to the day since the last day I saw my dad before he passed of Cancer when I was ten. I sat here breathing the crisp air and taking it all in. ‘I may never be back here’ I thought to myself, but I’m grateful I made it in the first place. There were so many thoughts rushing through my mind, yet there was a strange calmness about life itself. I was going to enjoy every second of that moment. The beauty and peacefulness of a world so far away brought clarity to the values and importance of my own life. Now, as I look ahead - I hope to find a way to make more of these great life moments. But why stop there? I want to bring these moments to others to share. I believe true happiness is shared. I don’t yet know how exactly I do this, but if you’re reading, you’re already part of my journey.

Thank you f-stop for being a part of my expedition, and sharing this story to the world, to help me on my quest not just to motivate, but to empower.

You can find Alex's work on his Instagram and Website.

"We Are f-stop" is for all f-stop users to share their stories from the field, from small daily adventures to epic travels. Contact us with your story on Facebook or drop us an email to [email protected] and let us know where your photography takes you and your f-stop pack!

SHOP ALL GEAR MORE WE ARE f-stop

©2022 F-stop

Ruandy is a photographer and videographer. If he had to pick a label he’d say he is an action sports/portrait photographer. Action sports are his favorite followed closely by portraits. He loves being capable of shooting anywhere with minimal gear. Desert, forest, street, studio or a tiny room he would look at any location as a challenge. He thinks that is what makes photography fun for him.

Words and images by Ruandy Albisurez

My photography adventure was in Guatemala. I flew from Los Angeles into Guatemala City from Aug. 28 - Sep. 10, 2019. My adventure was one part of working on a personal photo project and one part visiting family. My parents live just outside of Guatemala City and much of my family still reside there.

The trip was important to me because I had not been back to visit in around 15 years and the photo project I am working on is important to me as well. I want to shed some light on the action sports community in Central and South America for people in North America. I don’t feel they get enough attention aside from the occasional travel write up or video I see in digital magazines that don’t put any focus on the locals growing the scene, building parks, running shops and organizing events. And all of that is a lot tougher to accomplish in a third world country. There are many talented athletes that come from very poor backgrounds that I think could change their lives around with the right exposure. So part of my project is hoping that I can help open up some doors for some of these athletes and get them some well-deserved exposure. I flew down as a one-man show to see what I can capture and share with people.

The biggest challenge I was going to face was finding some local action sports athletes to hang out, get to know and shoot with. I began doing searches on social media to find athletes with content that showed some promise in front of the lens. I reached out to many and only heard back from a few but that was definitely enough to get my foot in the door and meet other athletes as well. Being where we were, there are not very many chances to get shot by a sports photographer for a lot of these riders. All in all, we were all having a blast. For myself, it was hanging out with these young guys and getting to know them and learn a little about their scene. And for them, it was the rush of doing the same trick on repeat until we’d knock out a good shot and we would all be stoked with the results.

The best moments of the trip were hearing about how the local bike community is growing and how they’re all coming together to get this park slowly built up. They are all busy working on ways to come up with the resources to accomplish their goal. They still continue to build when they can and little by little have been growing this small line of jumps you see in the images. This is a small section of the park that they were granted access to in the small town of Fraijanes. Their dedication shows and it is a healthy outlet for them that keeps them out of trouble. In time I hope to be able to work on some kind of program to possibly get a little bit of aid down to these guys and help them get their park completed sooner than later. It would be a great place for younger kids to have a place to get into the sport. Outside of the riders, I shot some images of the countryside, a local mountain bike park, and the people. In Antigua, I donated some time to a local foundation Ninos de Guatemala and photographed some of the students to help them use those images to get some new sponsors. Overall I had a great time and experience.

Tips I can offer for traveling and photography are just to know what the minimum gear that you need for the images you are trying to create, and have a good way to transport it all and keep it safe. My Ajna was perfect for the trip. I was confident I wouldn’t have to check the bag and if by some chance I did I was confident about pulling the large ICU out and throwing it under the seat in front of me like a worst-case scenario. Knowing that I have that option brought me lots of peace of mind as far as my gear. Honestly, I had no problem fitting my Ajna into the overheads on its side.

You can find Ruandy's work on his Instagram and Website.

"We Are f-stop" is for all f-stop users to share their stories from the field, from small daily adventures to epic travels. Contact us with your story on Facebook or drop us an email to [email protected] and let us know where your photography takes you and your f-stop pack!

SHOP ALL GEAR MORE WE ARE f-stop

©2022 F-stop

As a visual storyteller, Nick loves to just get out and try to challenge himself to get after a different perspective on capturing the moment. He says that there are so many ways to look at an individual story, but it’s all about the approach to define how that story ends up being conveyed. He actually enjoys the most going back to the same places repeatedly because it allows him to take a different approach each time. He really enjoys shooting the action sports world and he grew up shooting in the field quite a bit. Over time though, he has shot weddings, portrait work, product photography, commercial work, etc. Recently though, he has been really enjoying product / commercial photography and has been pushing himself the last couple years to capture those stories through different perspectives in that field.

Words and images by Nick Mitzenmacher

f-stop: Can you tell us what was the adventure about?

Nick: To be honest, this adventure was mainly just to get lost in the desert for the weekend.

I have been making it a mission to get out and challenge myself on some personal photo missions lately and just go get lost with camera in hand with good friends around. We really didn’t have a plan while we were out there other than shoot rad photos and find some locations we haven’t discovered out in a place we have been a few times before.

I had one of my best buddies join me for the adventure. He just bought a brand new truck and wanted to get out for some camping/shooting photos for the weekend so I agreed. I thought it is awesome to ditch the coast for a week and get lost in the desert with it being so close.

We have known each other since high school and have been learning photography together along the way so it’s always a good time to get out to shoot some photos with him. We are on the competitive side with everything it seems like too, so we definitely pushed each other to think outside the box to see who can get the best shot of the trip.

f-stop: What was your biggest challenge during the adventure, and how you overcame those challenges?

Nick: I would say the biggest challenge we faced during the adventure was timing. We only were out there less than 24 hours so we weren’t able to go a ton of places like we had originally wanted to be that we got lost quite a bit along the way. But hey, that makes it fun right?

I think half the fun is getting lost on trips like this. We went with the intent to capture photos along the way, but how you adapt to each location was what made it the most fun because we had no idea where we were going most of the time. We were getting lost deep in the desert. Once we found a spot we liked, we’d park the rig, hike up some random trail/hill/path and end up at some pretty awesome spots. If you asked me to show you where we took the photo though, definitely couldn’t remember how to get there.

I would say the biggest learning was to get lost more, it’s pretty fun because you end up some in awesome places that are unexpected.

f-stop: Can you remember some of the best moments of the adventure?

Nick: The best moment from the adventure was ending up at Hills of the Moon. It’s a snake run of washes that you 4wheel through, and as you get deeper the walls get higher and the roads get more narrow. Eventually, you can’t go any deeper into the canyons, and when you crawl up on the ridges, you look like you’re on another planet, which is why it is called Hills of the Moon. This was the one spot we had on the minds to get to but had very very minimal knowledge of even how to get there, so we just sent it and drove random routes until we ended up there where we thought it was.

f-stop: For the people that plan to visit Anza Borrego, can you share some tips and tricks?

Nick: Amidst all the chaos in life and how fast-paced everything is now and days, my biggest suggestion is to challenge yourself and just take time for personal photo adventures. Whether you are someone just learning photography or an experienced veteran, the best way to get better at your craft is to do it more!

f-stop: What gear did you use for this adventure?

Nick: I used the Tilopa pack along with the Medium Sloped ICU and Medium accessory pouch. I love the size of this pack when you want to pack all the toys and still have a bag that is light enough to hike with. I’d say it’s the perfect amount of space to gear ratio for everything you need to pack to get deep into the various vehicles won’t go.

For the camera gear side of things I had stashed in my bag:

• Nikon D810

• Nikon 35mm f/1.4 lens

• Nikon 70-200 f/2.8 lens

• Nikon 24-120 f/2.8-5.6 lens

• GoPro Hero7 Black

• GoPro Fusion

• Various GoPro Mounts

• Goal Zero Venture 30 Charger

• Pelican 0915 Memory Card Case

• 40oz Camelbak Chute Insulated Stainless Steel Water Bottle

• Jackets for when it got colder later in the day

• Snacks for days for any of the longer trails we got lost on

You can find Nick's work on his Instagram and Youtube.

"We Are f-stop" is for all f-stop users to share their stories from the field, from small daily adventures to epic travels. Contact us with your story on Facebook or drop us an email to [email protected] and let us know where your photography takes you and your f-stop pack!

SHOP ALL GEAR MORE WE ARE f-stop

©2022 F-stop

Discount Applied Successfully!

Your savings have been added to the cart.